Habitat

Born in Esher, Surrey, Terence Conran was educated at Bryanston School and studied textile design at London’s Central School of Art (now incorporated into Central Saint Martins) under Eduardo Paolozzi. The period also included time at the Rayon Centre in Grosvenor Square, as well as designer at Dennis Lennon’s studio, alongside first wife Brenda Davison — the union was short-lived.

After contributing designs to the Festival of Britain in 1951, Conran took a trip to France and was inspired to open an old-time soup kitchen with partner Ivan Storey the following year.

Located off Trafalgar Square, the Continental-style bistro served soups in blue and white striped bowls and espresso in brown pottery cups.

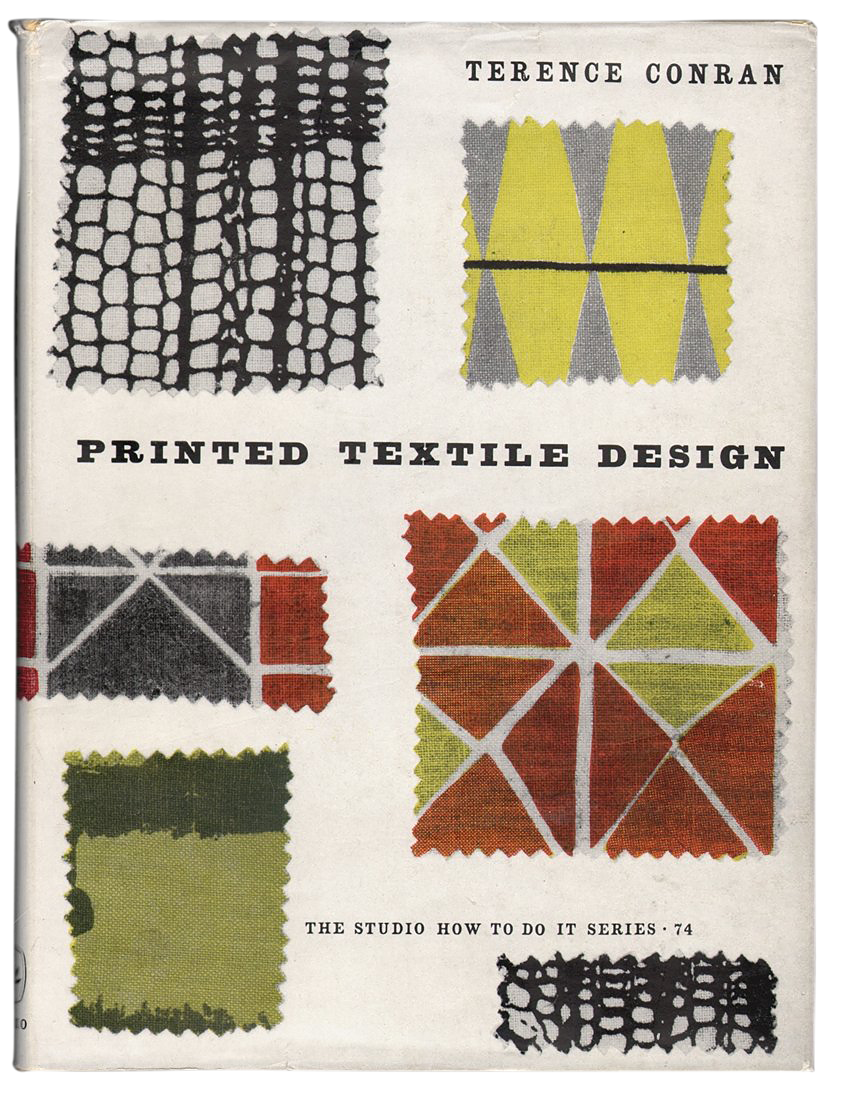

While studying at Central School, Conran sold his first design to David Whitehead’s Contemporary Prints, based in Lancashire. Conran would continue designing fabrics to firms including Liberty and Gerald Holtom.

The young industrial designer married Shirley Ida Pearce in 1955.

Pearce, a one-time painter, studied sculpting at Portsmouth Art School and worked alongside her husband as design assistant and salesgirl.

The pair formed Conran Design Group (CDG), which also included illustrator Anne Moorey on staff.

From factories in London and Manchester, the couple made office furniture and fabrics — some of which were exhibited at the Modern Interiors floor of Woollands department store in Knightsbridge.

Several designs were included in the ‘How To Do It’ series from The Studio Publications, which released Conran’s Printed Textile Design book in 1957.

The business expanded and by 1960, the firm had factories in Camberwell and Fulham, and an office in nearby Kensington.

By 1964, Conran, now married to journalist Caroline Herbert, had a thriving furniture and fabrics business, a new factory in Thetford, Norfolk. The firm also recruited designer Rodney Fitch.

Fitch became managing director of CDG until 1972, when CDG was sold to the Burton Group.

Back at Habitat, the company was busy doing contract work for companies such as Gillette, interiors for Harvey’s Restaurant in Bristol, and the “ahead-of-its-time” Jaunty restaurant in London. In addition to designing the British Exhibition in Moscow, CDG introduced the Summa wall-storage system.

Writing for The Observer newspaper in January 1964 etiquette author Drusilla Beyfus wrote “the entire set is an ingenious stroke of salesmanship — minimising installation costs, bringing into production a type of scheme that until now has had to be specially commissioned...”

Customers could purchase Summa singly or assembled for just under £200.

The success of this young company is especially interesting. Its consistent design policies, from the drawing-board through to the brochure, have crashed through the barriers of conventional thinking in the business and opened up a prospect of a brighter future for the whole industry.

The Observer Weekend review. Modern Living by Drusilla Beyfus. January 19, 1964.

Pot-and-Pan Revolution

The biggest change was about to happen. With little interest from retailers for his Summa self-assembly range, Conran did the next best thing — he opened his own store.

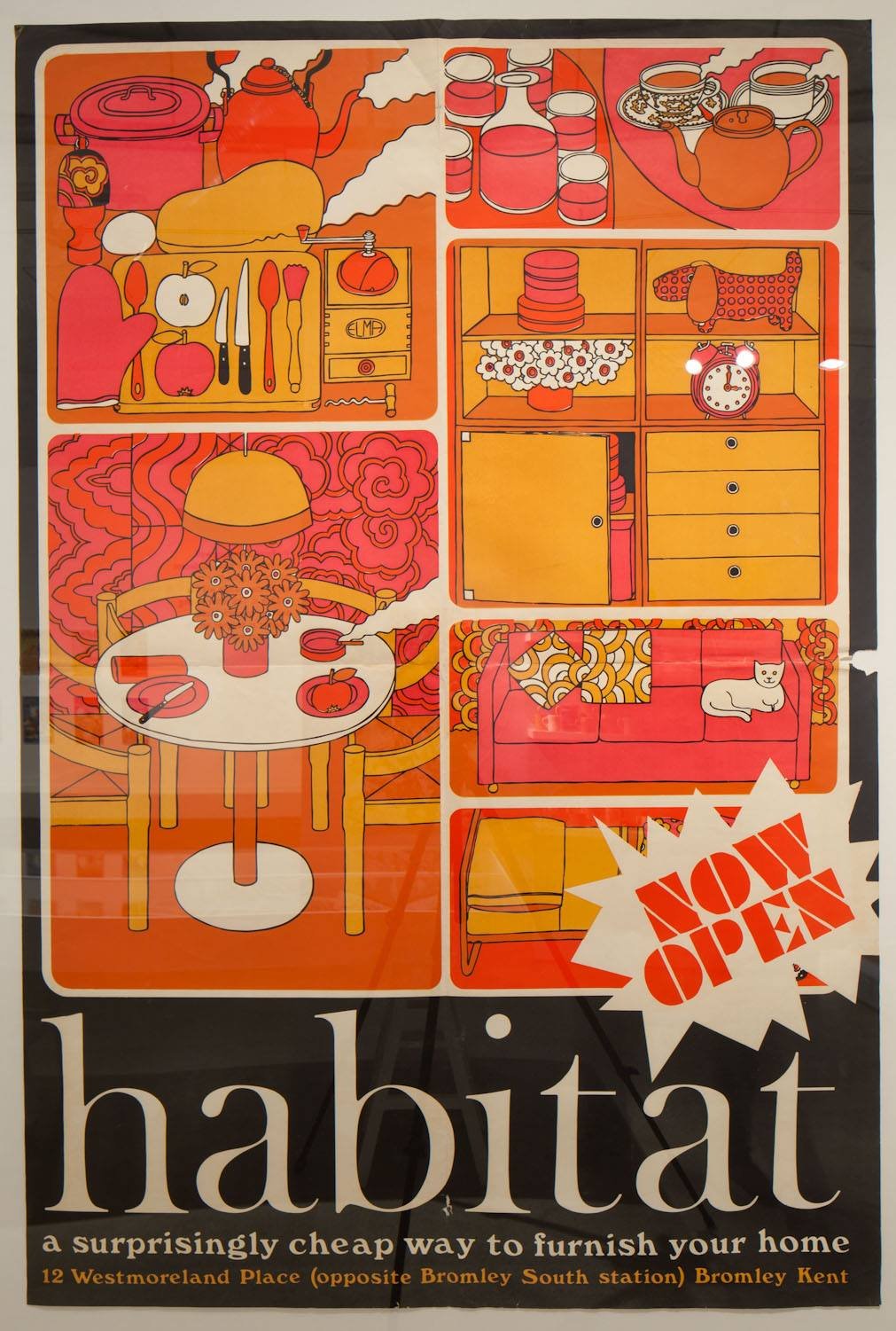

With its name supposedly an anagram of the Conran family cat, Tabitha, the first branch of Habitat landed in South Kensington in 1964.

Prior to the shop’s opening on Monday, May 11, the Sunday Times Home section groomed readers for the event.

Tomorrow morning, on the stroke of half-past nine, a heavy nine-foot tall oak door will pivot open and another new London shop will be in business.

With its folksy peasant aesthetic, the landmark shop on the unfashionable Fulham Road sold the total domestic look. The stores were bright, trendy, simple, and sensible, with interiors handled by Oliver Gregory and Colin Fulcher, better known as Barney Bubbles.

With Habitat's aspirational yet affordable products, it appealed to the post-war generation seeking independence from their parents.

The shop sold flat-pack furniture - or "knock-down" — a concept mastered by Swedish meatball pioneers IKEA years later.

The flat-pack furniture arrived with instructions, and all the parts could be carried out in a carton or ordered through catalogs. In addition to the friendly, serve-yourself atmosphere, many of the items were displayed in room sets, combining large pieces of furniture with small domestic accessories — a concept borrowed from French retailers of the time.

In Habitat, merchandise is clearly and slickly displayed. Chairs are lined up in racks and coffee pots in rows. Assistants are seen, not heard. You pick your wire basket and take what you like off the shelves. People obviously enjoy it.

Daily Telegraph. Feb 2nd, 1968. Margaret Duckett. "Conran's Own Habitat"

With staff in uniforms by Mary Quant and hair styled by Vidal Sassoon, the shop carried all the ingredients of pop decor; "furniture in light-coloured wood, boldly coloured fabrics in hectic patterns, country kitchen furniture and masses of rustic cooking equipment."

Conran’s team stocked the shop with imported French cookware, tableware from Italy, and Scandinavian furniture, capitalizing on the renewed interest in French and Mediterranean cooking ignited by Elizabeth David's French Provincial Cooking in 1960.

Several Habitat items, such as tea towels and pottery, carried distinctive designs by Juliet Glynn-Smith. The graphic designer was responsible for the illustrations in Habitat's first catalog (later designed by Stafford Cliff) and formed her own company, Hunkydory, in 1970.

Based in Kensington, Hunkydory produced a range of colorful, shiny, plastic-covered notebooks, notepads, and address books. The range was available at Habitat and Miss Selfridge.

'Prince of Quince', furnishing fabric, printed cotton, designed by Juliet Glynn Smith for Conran Fabrics, Great Britain, 1965.

The immensely successful store that encouraged pop patriotism spawned what Fiona MacCarthy for Britain's Guardian newspaper in 1966 called the Conran people.

They buy their lives from Habitat, the shop in Fulham Road which Terence Conran, great magician, filled with county air and copper pans amid milkmaids' churns in 1964.

The famous shop introduced Britain to designers that became household names and products that became ubiquitous, including the beanbag, fondue, wok (complete with instruction manual), and the Continental Quilt – better known as the duvet, inspired by a trip Conran took to Sweden.

Habitat sold chairs by Charles and Ray Eames and Robin Day alongside prints of recently commissioned pieces by artists including David Hockney and Eduardo Paolozzi. Other items included cookbooks by Caroline Conran, including London à La Carte and Paris à La Carte from 1967.

Among the top selling items was the T1, a tubular metal chair designed by Rodney Kinsman of OMK.

Live at ease, among things you can afford

Conran’s name and designs caught the attention of U.S. retail giant Macy's, who enlisted Conran on a line of household designs. In September 1968, the giant retailer took full-page ads touting the "brilliant British innovator of an unmistakable kind of home interior."

Telling readers they "literally imported Terence Conran's talent," Macy's was overjoyed at "the combination of British talent and American manufacturing techniques." The line occupied four levels at Macy's flagship store in New York.

In addition to lamps, towels, and bedding, the very "with-it" English designer's line of furniture was fabricated in the U.S. by Kroehler Manufacturing and called the line "contemporary furniture without gimmicks."

Back in Britain, the thriving Habitat emporia opened a second location in 1966 on London's Tottenham Court Road and added additional branches in Surrey, Bromley, Brighton, Manchester, and Berkshire.

The flagship store at 77-79 Fulham Road (which evolved into the Conran Shop in 1974) survived until 1988 when fashion designer Joseph took over the spot.

The firm entered the mail order market in late-1969 with Habitat by Post. Utilizing a customer mailing list from Habitat's six branches, it was hoped the 90-page catalog, photographed by Roger Bain, would bring in annual sales of around £1M.

A similar venture called Clothes Line, a few years later, featured leisure clothes for men, women, and children. Unlike the mail order catalog, Clothes Line was printed as a broadsheet.

During this period, Conran worked with Frederick Gibberd & Partners on designing Terminal 1 at London's Heathrow Airport.

As the recession hit the mid-1970s, Conran introduced Basic Habitat, a range of low-cost, entry-level products.

During the time Habitat flourished, Conran, along with Oliver Gregory (d. 1992) and art gallery owner John Kasmin, opened The Neal Street Restaurant in 1971, with menu designed by David Hockney.

It is rather difficult to explain why the Neal Street restaurant looks pleasant. The walls are white-painted brick, the floor plain quarry tiles. There is one sort of hollow, pillar space with ferns in it. Two slightly forlorn roses sit on each table. The chairs are our old bentwood friends, from Habitat, no doubt.

Quintin Crewe. Eating Out in London. The London Evening Standard. October 27, 1971.

The writer went on to say that on the night he went, the clientele included David Hockney, Tony Richardson, and Ossie Clark. The famed eatery in Covent Garden later became Carluccio's (operated by Conran's brother-in-law), which closed in 2012.

Looking like the inspiration for Heaven 17’s Penthouse and Pavement album, Terence Conran let the world know he mixed Canada Dry Ginger Ale with his Scotch. Ad from 1971.

After opening stores in France and Belgium, the chain debuted its first U.S. store in 1977. Located in the new Citicorp Market Center at Lexington and 54th Street in New York, the Manhattan store occupied two floors and operated under Conran's (a lighting company already served as Habitat).

Selling everything from paper light shades to modular seating, the store continued Conran's belief that buying furniture should be as easy as possible, opposing long waits for delivery, limited stock, special ordering, and complicated billing.

The company expanded into the suburbs with locations in Manhasset and Bergen County.

After authoring the acclaimed The House Book in 1976 (once considered a training manual), Conran followed up with the The Kitchen Book and The Bed and Bath Book. A third book in 1981, The Cook Book, was written with his second wife, Caroline.

The landmark book in home decorating is the gift par excellence for anyone of any age who is making a change in his living environment.

Eve Ernst, Los Angeles Times, 1977.

Life's Too Short to Stuff a Mushroom

Shirley and Terence Conran divorced in 1962. The mother of their two boys, Jasper and Sebastian, continued as designer and journalist, writing about good home design — primarily for London’s Observer newspaper.

At the start of the new decade, Conran and Vanity Fair writer Audrey Slaughter joined forces on a new magazine, Over 21.

The magazine "for women who have come of age, whose bra is not for burning" debuted in April 1972 and was sold a year later.

After a brief stay in Monte Carlo in 1974, Shirley Conran wrote the book Superwoman - a bestselling guide to household management for today's woman.

Among the helpful highlights for avoiding chores and making life easier was the suggestion to squash toilet rolls so that the center is oval. This way, the paper doesn't roll off as fast.

Published in 1978, the book for "every woman who hates housekeeping" was translated into nine languages and became a bestseller in Europe. The handy guide was followed up one year later with Futures — Conran’s new book on surviving life after thirty.

Princess Polyester

While U.S. sales of Superwoman fell short, Conran hit paydirt with her next book. In 1981, she signed a lucrative deal with American publishers Simon & Schuster for her first novel, Lace. Renowned literary agent Morton Janklow noted the deal was "somewhere in the neighborhood of one million dollars." — a staggering amount for a first novel.

Among Janklow's other seven-figure authors were Sidney Sheldon, Judith Krantz, Jackie Collins, Danielle Steele, and Barbara Taylor Bradford.

They were not alone. British publisher Penguin/Sidgwick emptied their pocketbook to the tune of $240,000, and Italy's Mondadori shelled out $50,000.

When completed in the spring of 1981, Shirley Conran's novel was revised at the behest of Michael Korda — editor at Simon and Schuster, who advised the author to chop 50,000 words.

Published in August 1982 and referred to as junk food fiction, the steamy roman-à-clef quickly landed on the best sellers lists on both sides of the Atlantic.

Negotiations with Lorimar (the creators of Dallas) had already begun. According to the author, they bought the rights three days after seeing the manuscript for "a million dollars, plus, plus, plus."

In February 1984, the five-hour epic aired over two nights. It went up against the first television showing of Star Wars on a rival network, CBS — which filled the three-hour time slot with a 22-minute featurette.

Reviews for Lace were not kind. Howard Rosenberg for the Los Angeles Times wrote, "There's gold in garbage...", while John Leonard for New York Magazine said “… Lace is shameful, but Phoebe Cates is worth looking at for five hours. She curls the toes. She sulks like Messalina…”

Regardless, the international sex and seagulls T.V. drama, which also featured Angela Lansbury, produced the show stopping line uttered by actress Phoebe Cates, "Which one of you bitches is my mother?"

Arise!

The 1980s were a busy period for Terence Conran. The successful housewares company he founded was floated as a public company, which later saw Conran release about £2M worth of shares to endow the Conran Foundation — which subsequently set up the first Museum of Industrial Design. Directed by Stephen Bayley, the independent project was located in the former Boilerhouse yard of London's Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A).

We created a simple white box that would become our home for the next five years, putting on something like twenty-five exhibitions with a vibrant and questioning approach. We became very popular very quickly, and we certainly learnt a lot about how to create a really serious museum.

The start of the 1980s brought an outbreak of expansion and takeovers. With 53 stores worldwide, international franchising reached Japan — where Habitat Basics operated, and would start trading in Hong Kong in 1987.

After Habitat went public in 1981, Conran joined forces with Hepworth Menswear to create fashion store Next. More ambitiously, Conran acquired children's clothing store Mothercare, a chain with over 400 shops.

Founded by Selim Zilkha, the babywear chain faced competition from Boots, Marks and Spencer, Littlewoods, and C&A. Being careful to call the business agreement a merger and not a takeover, Zilkha said the goal was to give Mothercare an upmarket push, Habitat-style.

Toward the end of 1986, Conran’s goal of transforming the British high street was realized with the acquisition of British Home Stores (BhS) — a downmarket version of Marks & Spencer, and formed a new holding company, Storehouse Group.

Located in the Heal's Building on Tottenham Court Road, the Storehouse conglomerate comprised of The Conran Shop (soon to relocate), Conran Design Group, Habitat, Heals, Richards, SavaCentre, StoreCard, anonymous, and ConranOctopus.

With over 100 branches, the 58 year-old BhS was given a multi-million pound facelift, new logo, dropped their food items and focused on fashion and home products.

The Habitat magic failed to permeate the 900 stores, which counted roughly 34,000 staff. Customers complained of poor quality at Mothercare, while the ongoing revamp at BhS struggled to attract new customers.

Amidst falling profits, the sharks were circling and Conran escaped a number of takeover bids. At the beginning of the 1990s, a large number of Habitat stores vanished from the U.K. high street.

The ailing Habitat was acquired in 1992 by Ikano, a sister group to IKEA — a costly move, and subsequently taken over in 2016 by British supermarket giant Sainsbury's.

Sir Terence sold two-thirds of his stake and resigned, rejecting the City’s verdict that he was a gifted designer but an incompetent businessman. Adding to the misery was the collapse of Conran’s development company at Butler’s Wharf — the “city within a city” planned for the 12 acres of land next to London’ Tower Bridge.

Nevertheless, the man who said “Good design should be available to everyone” retained control of the Conran Shop. On the home front, the resilient designer divorced his third wife, Caroline Herbert. The former Lady Conran walked away with a much publicized sum, thanks to her significant contribution to her husband’s wealth — a notion not shared by Sir Terence.

The couple remained amicable and the resilient designer shifted his focus to gourmet chic.

Inside Bibendum restaurant at Michelin House, Fulham Road, photographed c. 1993. Photo: Wikipedia/DRD

Working with partner and Octopus publisher Paul Hamlyn, the pair polished up a 1910 Grade II-listed building in Fulham — purchased by Conran and Hamlyn two years prior. Located in the former home of the Michelin tire company, Bibendum restaurant opened in late 1987 — albeit with a slightly slimmer Michelin Man logo.

The stately building also featured a relocated Conran Shop and Bibendum Oyster Bar on the lower level, which only had seven tables.

Two years later, Conran officially entered the Southern California space with his first West Coast store.

Located on the ground floor of the Beverly Center (then anchored by Bullock's and The Broadway), Conran's Habitat in the giant West Hollywood mall only survived four years. Locations in Brea and Burbank soon closed their doors.

The Beverly Center, circa 1988.

The Manhattan-based chain cited declining sales and high operating costs. It sold its operation to new owner Marvin Traub (who also owned Bloomingdale's) — though its seventeen East Coast locations remained, with new stores planned for Boston and Connecticut.

Overnight, the pale wood dressers, Haseena rugs, and ceramic platters were replaced by Versace and Moschino duds when the 50,000-square foot space became Bullock's Men's Store.

The economic slump also affected several Southern California retailers: Barker Brothers, R.B. Furniture, Ortho Mattress, WJ Sloan, and Furnishings 2000, all closed or retreated to bankruptcy court.

With several successful restaurants under his belt — including the Butler's Wharf Chop House, Conran's next gastronomical venture was a former 1920s hotspot in London's upmarket St. James neighborhood. Inspired by French brasseries, the revamped Quaglino's reopened on Valentine's Day in 1993.

The next addition to the restaurant empire became London's largest restaurant, Mezzo, on Wardour Street. With room for 700 diners, the Soho eatery comprised two restaurants with 100 chefs, a bakery, and three bars. The restaurant was a family affair, with color-coded staff uniforms designed by Conran's son, Jasper.

The father of informal modern furniture remained connected to his roots with a line of Design by Conran furniture and lighting, available at U.S. chain J.C. Penney's.

By 2002, the store's branding had sold off the 'table and chairs' imagery and rebranded by the London-based design group Graphic Thought Facility. The original logo with Baskerville typeface was retained, but now included a heart mark.

That same year, the King’s Road location received a fresh coat of paint, and Habitat’s 71-year old founder launched Content by Conran, his first mass-market line of furniture since the 1960s. Conran stepped down as chairman of Conran Holdings in 2015, passing the business to son Jasper — already operating Conran Shops.

Staying active, Conran was busy with a new restaurants in Covent Garden and Shoreditch, as well as designing for Marks and Spencer (M&S), and preparing for the Design Museum’s new space in the former Commonwealth Institute in Kensington.

In 2020, one year after troubled Mothercare closed its last remaining U.K. shop, Terence Conran, the self-described "socialist of the Burgundy variety," died at the age of 88.