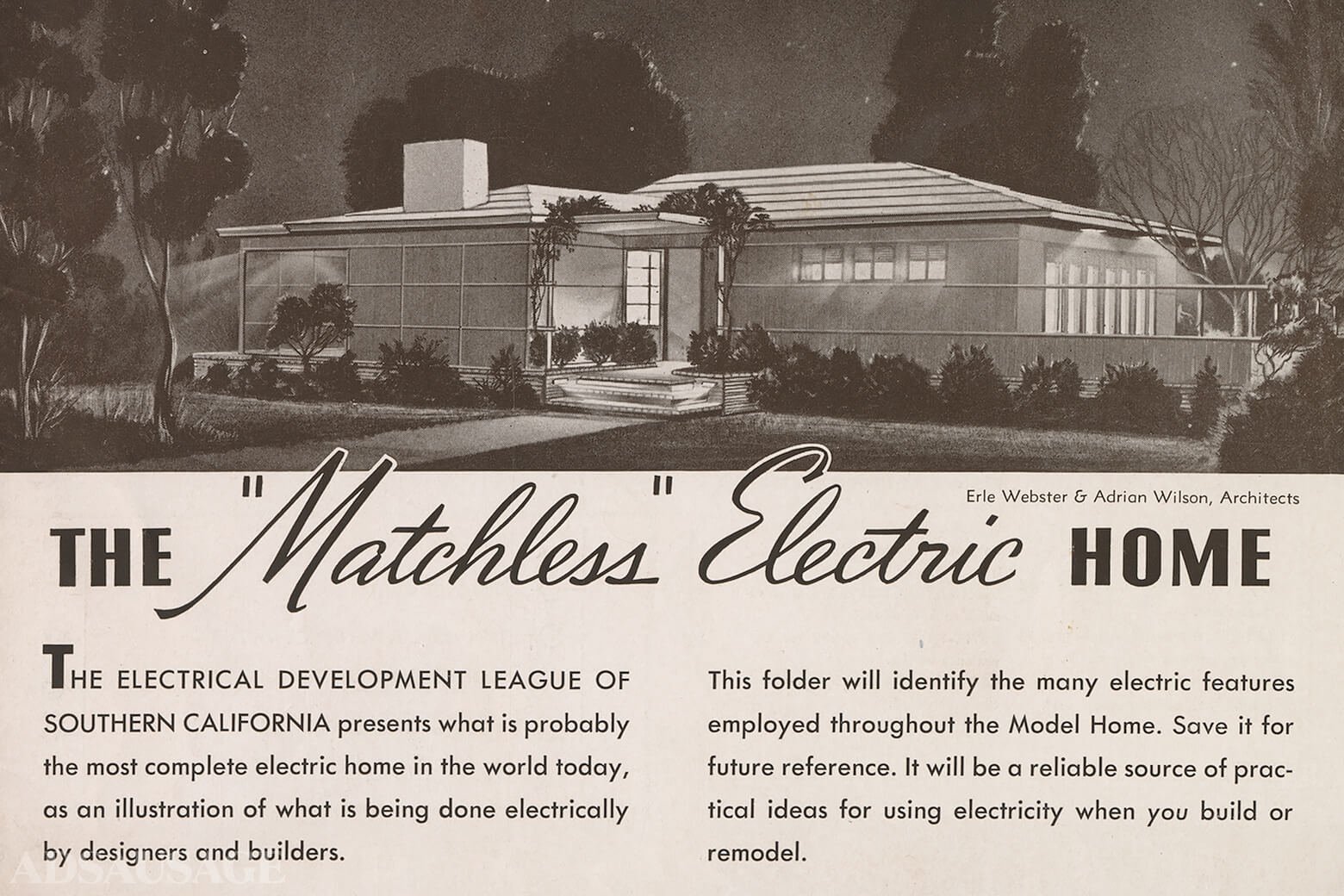

Live Better Electrically

The 1950s saw a period of significant economic growth and prosperity. The postwar era ushered in the “Baby Boom” generation, creating a surge in housing demand. Families sought larger homes to accommodate their growing households. The housing boom addressed that need by providing spacious homes suitable for families.

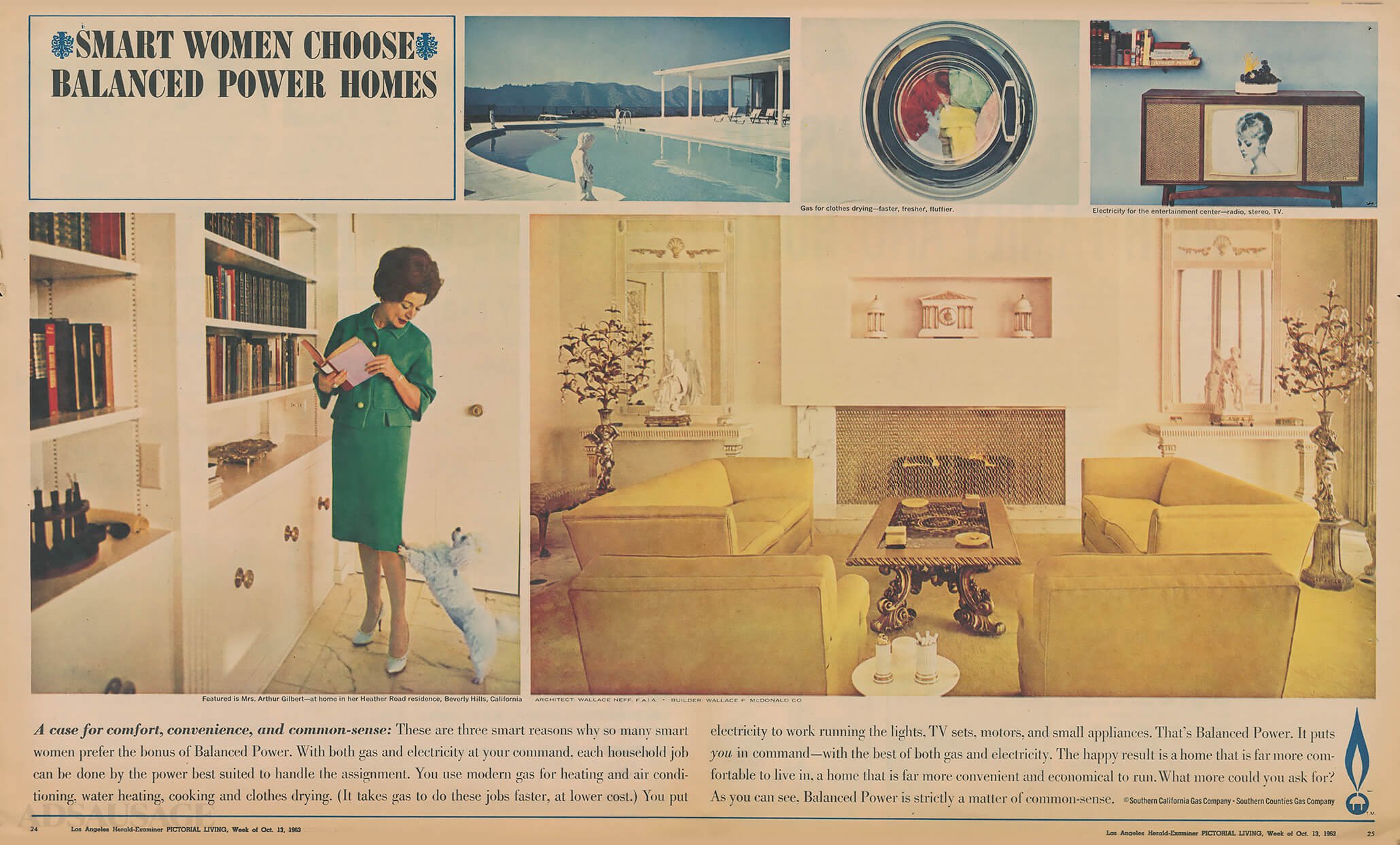

Gold Medallion Home award, 1964. Photo by Joseph Fadler.

Southern California Edison Photographs and Negatives, Huntington Digital Library.

Many of those homes built during this era showcased mid-century modern design elements, emphasizing simplicity, and functionality.

In response to rising demand, utility providers sought to enhance efficiency in production by constructing additional power plants, several of which were coal-fired. With the increased power output from these electrical plants, homeowners were incentivized to consume more electricity, resulting in reduced costs for higher usage.

With the rise of electricity in households, major players in the industry such as Edison Electric Institute, PG&E, CPU, and General Electric saw an opportunity to promote electric living and profit from this growing trend.

Back in 1957, the industry initiated the Live Better Electrically (LBE) campaign, which popularized the well-known slogan that had been loosely used in advertisements since the 1940s. This campaign was aimed at promoting the idea that electricity was the fundamental factor for improving the quality of life.

The well-known slogan was widely adopted by popular brands like Frigidaire, Thermador, Kelvinator, Hotpoint, GE, and RCA Whirlpool for their print advertisements, which were distributed nationally.

Nationwide Medallion Home Program.

The objective of the program was to encourage the development and sale of newly constructed homes that offer complete house power, lighting for daily use, and electrical appliances. Houses that met the criteria of being all-electric, having a range, water heater, dishwasher, dryer, electric heating, waste disposal, and refrigerator were awarded bronze medallions.

In addition, residential properties were mandated to include a service entrance that could handle 100 amperes — sufficient for the smooth functioning of electrical devices. The entrance should also have a minimum of 20 circuits, switches, and outlets to meet the present and future requirements.

“You just flip the switch in your home… and electricity is ready!”

The tireless electrical servant with the moniker, Reddy Kilowatt, had been in use since the mid-1940s. The happy and efficient little fellow was introduced to Southern California residents as part of Edison’s wartime conservation effort.

The cartoon figure was drawn by graphic designer William Gilchrist Meek (d. 1987), whose work also included the famous VJ day poster showing Japan’s rising sun sinking in to the sea.

Builders who incorporated electric wiring and appliances into their new homes were offered an allowance by Southern California Edison. The company also established "electric living centers" in their offices to educate homemakers on the proper use of electric appliances.

In Los Angeles, the first all-electric GM model home was exhibited at the LA Home Show. Held at Pan Pacific in June. Designed by Barton Bosworth. Built by Raznick & Sons of Granada Hills.

One such home — “designed for desert, mountains, or beach living”, was featured at the Decorators Show at Pan Pacific Auditorium, then put on display on Wilshire Blvd., and opened to the public. Designed by Ralph and Jane Bonnell, the 400 square-foot Gold Medallion home was known as “Holiday House”.

The national push extended to the Eastern Seabord, where utility company Niagara Mohawk boldly proclaimed “Electric heat is a completely dirt, dust and soot-free way to heat your home!”

Located in Amherst, New York, one of the first Total Electric homes on the East coast remains mostly untouched. And Florida wasn’t shy either — one contemporary home could be found in Temple Valley, Florida.

The “Gold Medallion” campaign aimed to sell 20,000 all-electric homes by 1958, 100,000 by 1960, and 970,000 by 1970. Considered a success, it was estimated that the goal of one-million all-electric homes was achieved.

Of course, in places like Southern California, extremely warm weather brought contradicting behavior from utility companies. During heatwaves, residents were advised to cut down on the use of electrical power — which baffled the very people who were once told to live better electrically.

The situation became more complex when the Southern California Gas Company opted to generate electricity starting in 1972. Their experimental fuel cell power plant in El Segundo transformed natural gas into electrical energy, offering a cleaner alternative to a gas-fired, steam-electric generating station and reducing pollution.

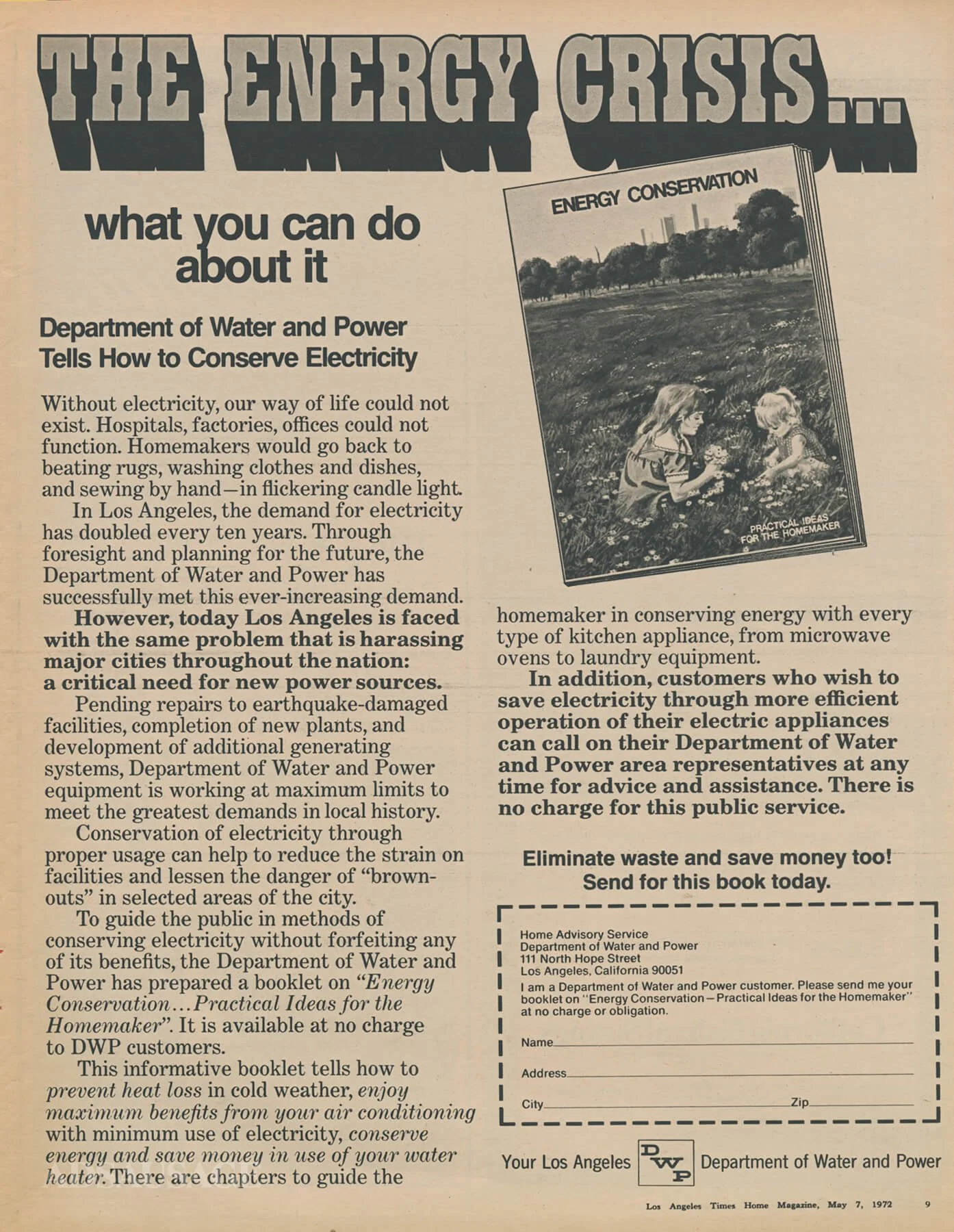

Crisis? What Crisis?

During the 1970s, the escalation in energy prices spurred a shift in the stance of energy companies. The detrimental effects of burning fossil fuels and the potential hazards of nuclear power plants raised concerns for the environment and safety.

By the mid-1970s, the tide had turned. In California, utility companies banded together in an effort to get customers to curtail useage and use less juice. To reach the youngest consumers, the Federal Energy Administration created a new hero… a hand-drawn symbol called “Energy Ant”, created by designer Tony Ranfone, a former combat cartoonist in Vietnam.

In Los Angeles, matchless homeowners found themselves with skyrocketing bills thanks in part to the LA DWP’s restructuring of its rates. Those long-standing all-electric homeowners who once received a flat or reduced rate now found themselves in a different semi commercial category.

The impact was made worse when the city experienced a particularly cold winter in 1979 — the coldest in more than 50 years. Critics argued that bulk-rate discounts for power users weren’t justified in the new energy-conscious age.

By 1980, a $1M low-interest loan program was approved and aimed to assist LA DWP customers save on their energy bills. Spearheaded by Councilwoman Joy Picus and Councilman Zev Yaroslavsky, Proposition E prioritized Gold Medallion home owners, which numbered around 40,000 people.

We’re placing emphasis on them in hopes that owners of these homes will be able to convert to solar or other nonexpensive [sic] types of energy generators.

Zev Yaroslavsky, 1980.

The energy challenges faced by the LADWP in the 1980s were part of a broader trend affecting utilities and energy systems in various parts of the United States during that period. As a response to the crisis, there were efforts to invest in new power plants, improve energy efficiency, and address the financial stability of the LADWP.

The notion of solar wasn’t new to the Los Angeles. Four years earlier, when the city held the first Energy Fair at the Los Angeles Convention Center, Mayor Tom Bradley remarked he would like to see Los Angeles become Solar City.

During this time, the state Public Utilities Commission (PUC) mandated a certain level of conservation advertising, and utility company San Diego Gas & Electric Co. (SDG&E) actually won advertising awards for their conservation campaigns, which included “There may be a short in the electrical supply this summer.”, and “Wasting gas is money up in flames.”

The 1973 OPEC oil embargo revealed the vulnerability of Western nations to their dependence on imported oil. It prompted these countries to reassess their energy policies and look for alternative sources of energy, such as nuclear power and renewable energy. The embargo also led to increased exploration and production of domestic oil resources in countries like the United States.

The oil embargo of the 1970s, which led to a significant increase in oil prices, prompted urgent responses to conserve energy. Governments, utilities, and regulatory bodies collaborated to implement measures to reduce dependence on oil and enhance overall energy security.

These efforts had a lasting impact on energy policies and practices. They helped shape a more energy-conscious mindset and influenced subsequent efforts to address environmental concerns and promote sustainable energy practices.