The Todd Killings

In April 1969, New York-based production company National General Pictures (“NGP”) proudly announced its upcoming slate of thirteen major films — calling it a “ringing affirmation of faith in the motion picture economy.”

With a home office in Hollywood, company honcho Irving H. Levin exclaimed that NGP became associated with several “exciting talents”, including Jacqueline Bisset, Jim Brown, Garry Marshall, Carol White, Billy Friedkin, and Barry Shear.

One of those upcoming titles was “The Schmid Case,” based on Charles Schmid, the Pied Piper of Tucson.

The story you are about to see is a fictionalized dramatization of actual case histories. The names and certain characterizations have been changed to protect the innocent and in some case to protect the guilty.

The Todd Killings, 1971.

Production

Director Barry Shear honed his television music style on a summer replacement series, The Lively Ones (1962–1963) — a musical variety program sponsored by Ford and broadcast on ABC.

After being signed to a five-picture contract at Columbia Studios in 1964, Shear continued a variety of other projects which included producing the Hollywood Pavillion exhibit at the

New York World’s Fair.

The busy New York-born director was then tapped to develop a late-night talk show for ABC — set to compete with Steve Allen, and Johnny Carson (then in its third season). The result, The Les Crane Show.

Working steadily on the small screen, Shear landed his first feature film in 1967 — a protest drama for American International Pictures.

Opening in July 1968, Wild in the Streets featured an all-star cast, and garnered positive reviews.

Prior to its European release, the “generation gap” movie became AIP’s highest grosser. Film critic Kevin Thomas for the Los Angeles Times noted, “Barry Shear directs with enormous drive, authority and imagination.”

After a hasty departure from The Beautiful Phyllis Diller Show for NBC, Shear was planning his next picture — a project with writer Harlan Ellison called Swing Low, Sweet Harriet. While that never materialized, it was reported in early 1969, that National General Productions signed Shear for The Schmid Case.

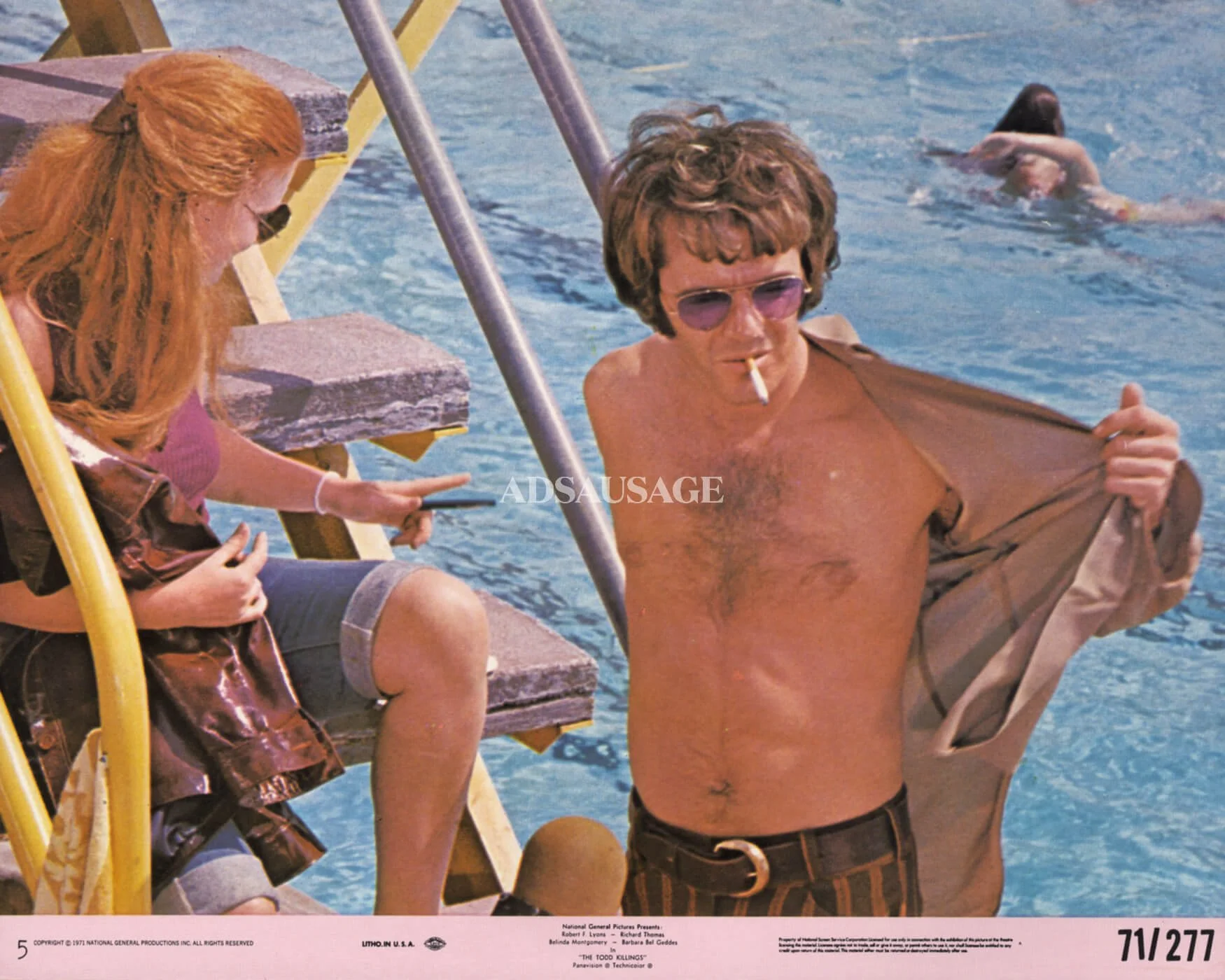

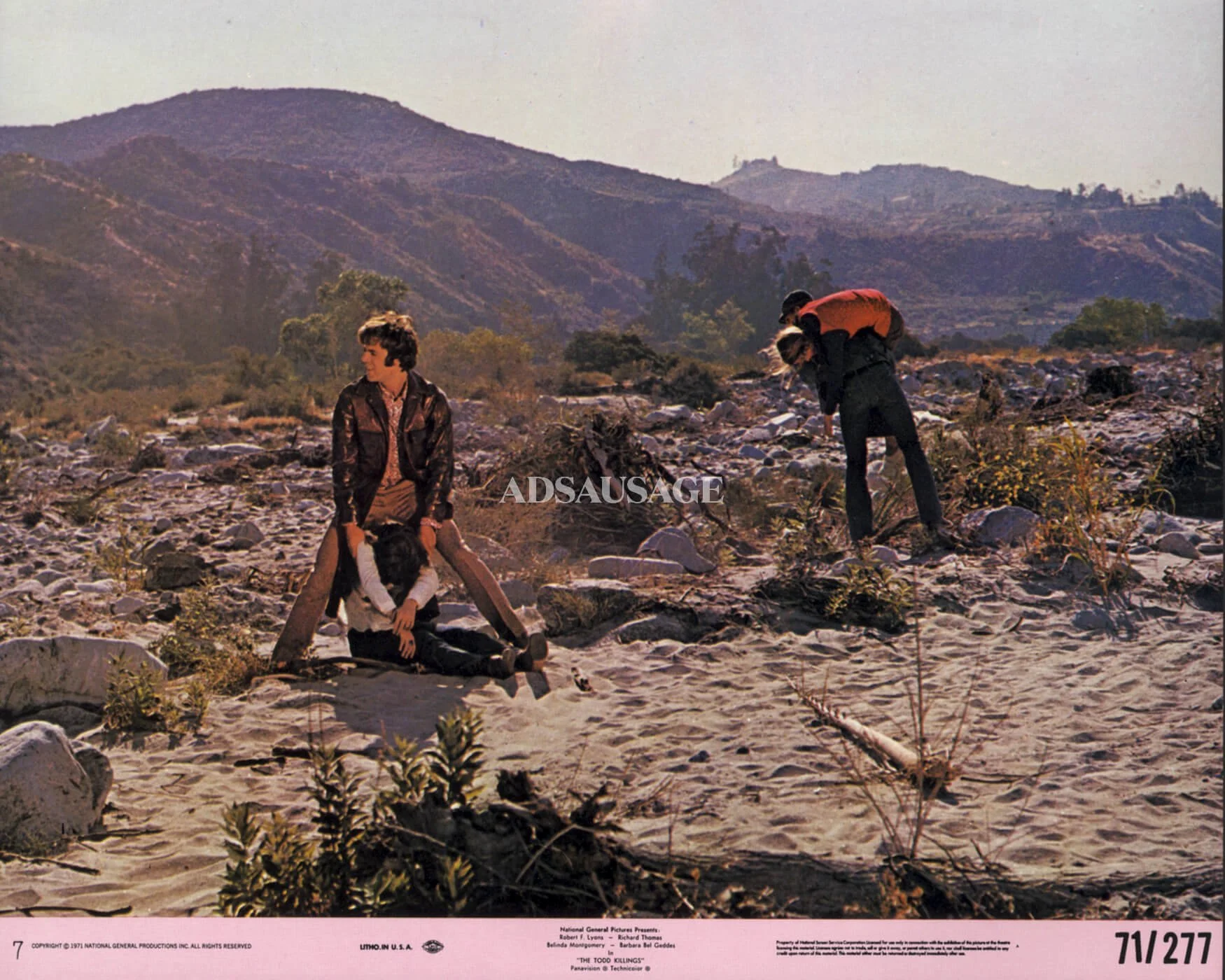

Shear was interviewed in May 1970 for the Anaheim Bulletin, telling Barney Glazer, “We want to avoid any identification whatsoever with those cheap and shoddy “Beach Party” and “Motorcycle Gang” exploitations.”

The article also noted that the movie used locations including the Verdugo Hills Pool in Tujunga.

Our characters are not typical bad kids, today they’re just about average, I’d say, in their preoccupation with drug and sex experimentation. We intend to show the delinquency and crime jump from the ghetto to middle class neighborhoods.

Barry Shear, May 2, 1970.

Of the many changes taking place during production, Barry Shear replaced British director Alastair Reid. Coming off the 1969 curio, Baby Love, Reid’s involvement in his first American feature, involved scouting locations in early 1970. Along with producer Abby Mann, Reid favored Albuquerque and Las Cruces as possibilities for the new picture, then called Pied Piper.

While the pair were scouting for the murder story, two early leads were cast: Richard Summers and the producer’s wife, Harriet Karr. Sharing company with Alistair Reid, these two names would also be cast out.

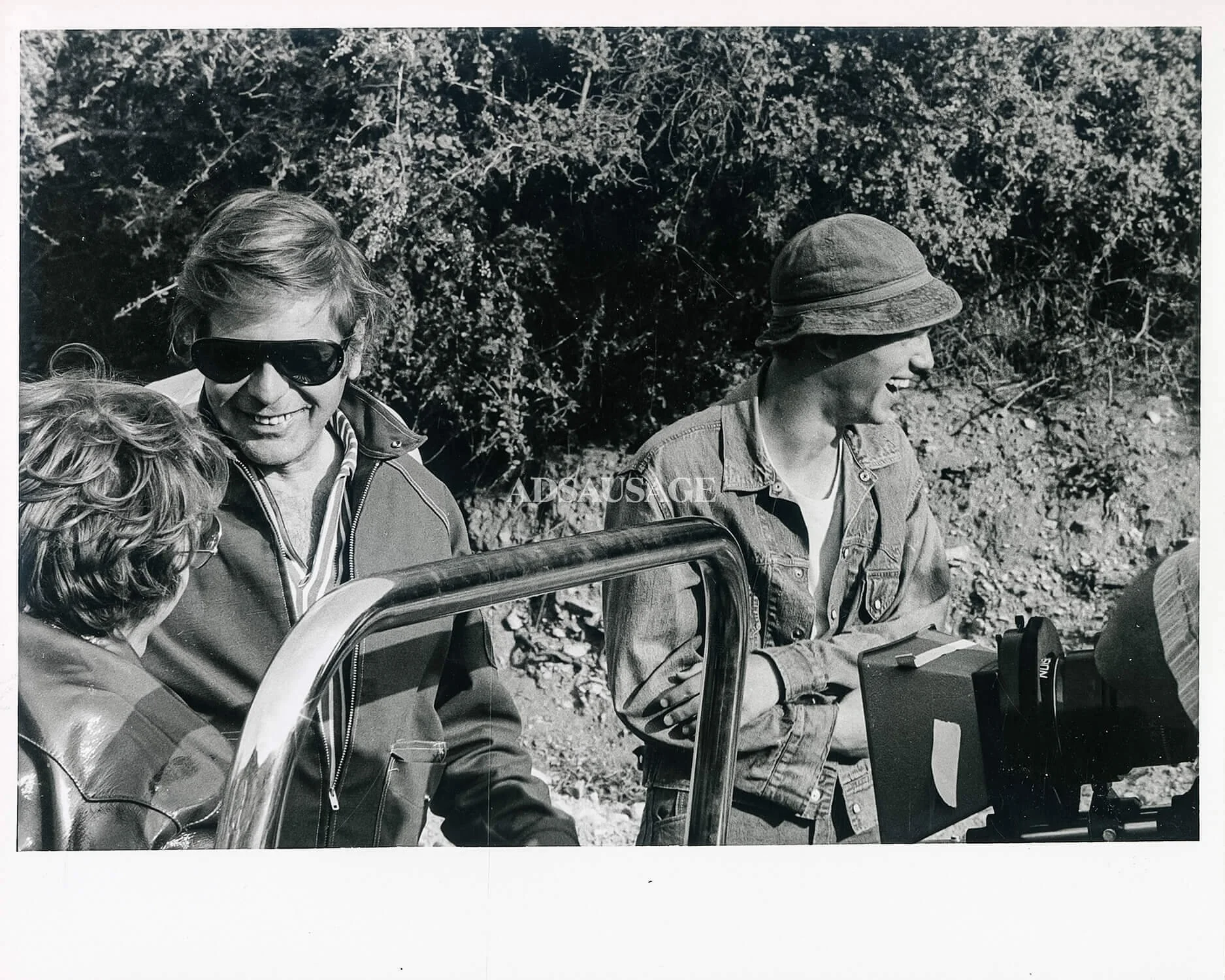

Director Barry Shear, on the set of The Todd Killings, 1971.With a budget of approximately $1.8M, the crew utilized the Lincoln Heights Jail, to the tune of approximately $10,000. Abandoned since July 1965, the set designers gave the cells, booking office, and visiting room a makeover. An economic move that paid off.

Not surprisingly, the film went through a variety of titles; "Pied Piper", "Skipper and Billy Boy", "The Modern American Burial Society" and "Running Scared." Eventually, the "contemporary drama" had its title chopped down to "Skipper" before settling on its final release title.

CAST

Under its former name, “What Are We Going to Do Without Skipper?” the majority of the cast signed on around May 1970. Casting included Gloria Grahame — now semi-retired and living in the San Fernando Valley with her family. Although Grahame remained busy with mostly television roles, newspapers were eager to note this was her first significant role since Oklahoma! in 1955.

Veteran actress Barbara Bel Geddes — who remained active in painting animals — had completed filming Anthony Newley’s big screen version of Summertree before her role for producer Abby Mann.

Around this time, Abby Mann’s time on set was decreasing. Mann’s new wife, Off-Broadway actress and former model Harriet Karr, was replaced. The studio reportedly commented with a straight face, “It’s a combination of many things, like she wasn’t feeling well and we decided someone would be better in her place.”

The young actress must have taken ill a few years later, when reports noted Karr was up for her big screen debut in the 1975 police crime drama, Report to the Commissioner, written by her husband.

The couple divorced in 1978.

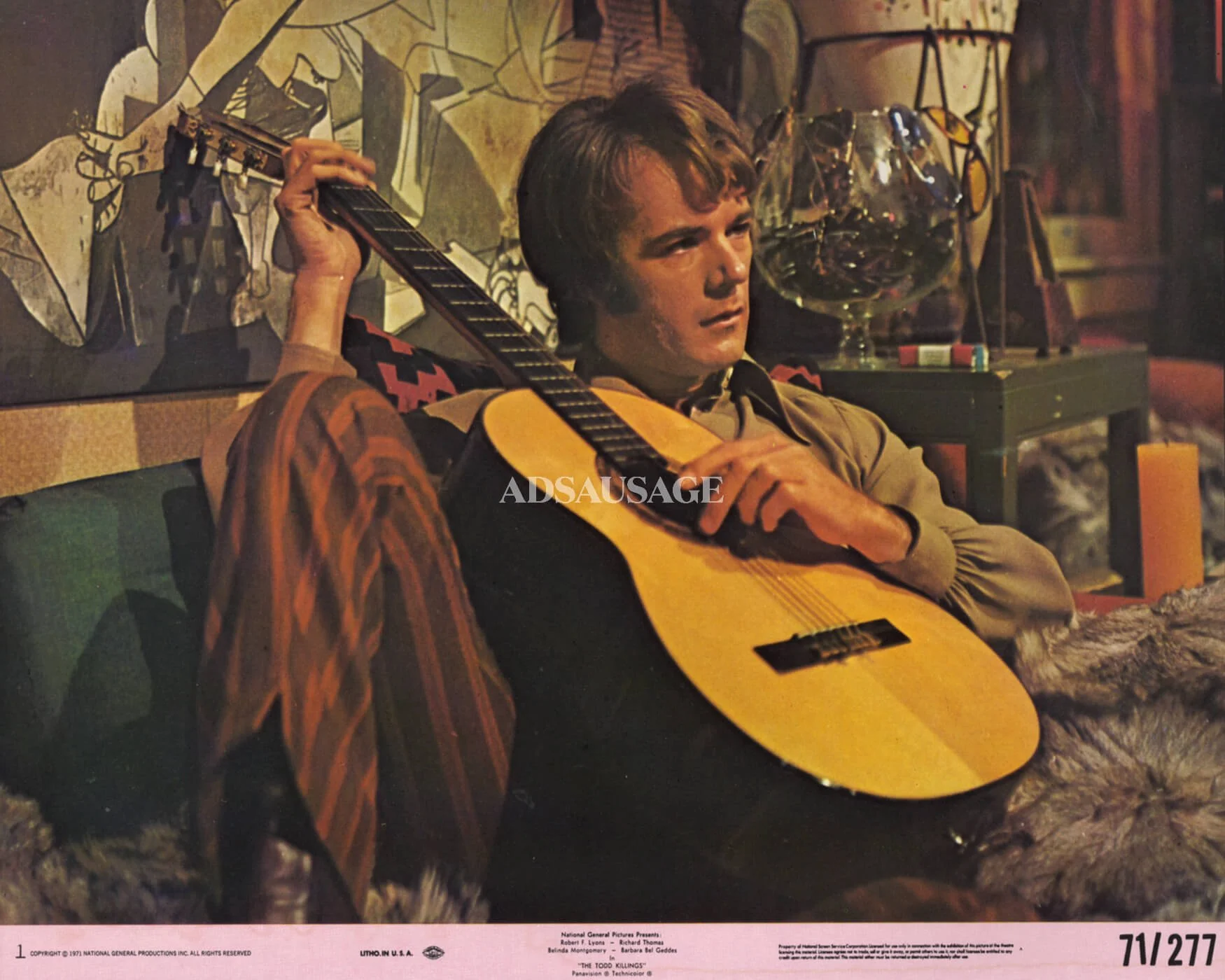

Rounding out the cast were; James Broderick, Ed Asner, Robert F. Lyons, Richard Thomas, and Sherry Miles.

Signed to a multi-picture deal for National General, the gorgeous Honolulu-born actress and Punahou Preparatory School graduate, Miles (born Sherry deBoer) appeared in West Coast spots for automaker Dodge and became a cast member of the revamped Hee-Haw.

The upcoming local told the Honolulu Star-Advisor in 1970 that she regretted changing her name to Miles — something she got from a Robert Frost poem.

After getting married in 1973 to Dennis Michael Murphy, Miles racked up a few more credits before leaving the entertainment world. Heiress to the Longs Drug fortune, Sherry deBoer lobbied for animal welfare, founding the Animal Health and Safety Association in 1990.

Another rising star was Toronto-born Belinda Montgomery. The stunning actress appeared with future co-star Richard Thomas in episode of ABC’s Marcus Welby (“Echo of a Baby’s Laugh“) in October 1969.

Although signed to Universal Studios, Montgomery remained active on the small screen and was loaned out for spots on CBS Playhouse and M-G-M’s Medical Center.

Her busy television schedule included the fairytale spoof Tales from Muppetland (“Hey Cinderella”) in April 1970. Shown on ABC, the live-action program by Jim Henson was reportedly filmed two years earlier.

The Albany, New York-born Robert F. Lyons gaind good notices in Pendulum and Getting Straight. By 1970, Lyons was a San Fernando Valley resident and a member of the Actors Studio.

The family man enjoyed comedy, which led to his creating the Key Out Players - an improvisational group of five players. The troupe made an appearance at the Hollywood Center in June 1971.

The oddest casting choice went to Ed Asner — then known for his work on the CBS show Slattery’s People. The network liked what they saw. Jim Brooks and Allen Burns signed Asner to play the irascible Lou Grant on The Mary Tyler Moore Show, which bowed in September 1970 on CBS.

With a handful of titles under her belt, Holly Near was added to the cast. The former UCLA drama school student continued acting and performing in interesting projects, such as F.T.A. with Jane Fonda in 1971. The political vaudeville anti-establishment revue had a benefit at the Ash Grove in Los Angeles. The red headed folk singer joined Jane Fonda for the song and dance number, “Nothing Could Be Finer Than To Be in Indochina.”

Two minor but curious casting choices included KNXT newscaster Clete "The Big News" Roberts as a courthouse reporter and former boxing champ Sugar Ray Robinson as a cop.

Composer and arranger Billy Goldenberg was attached to the soundtrack, as were Mort Garson and Jacques Wilson. All three would exit, ultimately seeing Leonard Rosenmen credited. As it was, Goldenberg scored the music for the 1971 CBS TV-movie, The Homecoming, co-starring Richard Thomas as John-Boy Walton.

Reception

The Todd Killings had its World Premiere on August 18th, 1971, at the Arcadia Cinema in Philadelphia. Then, showing "Death in Venice" on the marquee, the Premiere was a small affair. The only cast member to appear in person was Richard Thomas.

Perhaps it was fitting to debut in America's Garden Capital — the films' producer, Walter Wood, hailed from Prospect Park. Speaking to the Delaware County Daily Times in mid-1971, Wood exclaimed, "I've looked at the influences being exerted by people like Charles Manson. I wanted to shakes up the parents a little bit. So this is a story about a young man who influenced a group of youngsters"

Regional newspapers were indifferent at best. The Philadelphia Daily News made its intentions clear, showing empathy instead for the neighborhood Arcadia movie house (which closed its doors seven years later). Movie critic Joe Baltake called the World Premiere a "dubious honor" for the shamed theatre.

Having already labeled the movie "a scatter-brained, oafish crime drama," Baltake saved his ire for director Barry Shear, holding him responsible for the movie being "without style, color, shape, or even shock."

The movie received similar treatment across the country. The Miami News woefully reduced the plot to a "ghoulish story of a young man who takes girls into the woods for purposes other than birdwatching."

Elsewhere in The Magic City, the Miami Herald howled, "With a Minimum of Planning You Can Miss Todd Killings.'"— and concluded its' scornful review with, "… the whole thing has about as much substance as a Hot Wheels commercial, as much originality as a McDonald's hamburger stand."

The hits kept coming. The Pittsburgh Post Gazette took exception to the "nasty" film and the cinematography, saying it appears "everything seems like it is being filmed in a steambath."

However, common sense came from longtime movie critic Kevin Thomas. Writing for the Los Angeles Times, the critic sharply observed the showcasing of French horror, Daughters of Darkness, as "the double-feature sleeper of the year," saying the movie "was one of the best of the so-called 'youth pictures'…"

Thomas praised Barry Shear and his gifted writers, reserving special praise for Shear, noting "his handling of actors is superb… and Lyons is a tour-de-force, alternately appealing and repellent, pathetic yet hateful."

Prominent film critic Rex Reed was somewhat upbeat, calling the picture "mildly fascinating," and observing the likable cast, including "the enormously talented new actor named Robert F. Lyons," giving the movie "more tension and bites than it warrants."

Three years earlier, co-star and vocalist Holly Near was interviewed by movie critic John Crittenden (“Cool to Stardom”). Referencing her handful of movie roles, Crittenden unfairly said The Todd Killings “is not worth remembering.”

Aftermath

Developed in 1961, NGP had its’ formation a decade earlier at 20th Century Fox studios. The company was created to acquire a theatre chain, then owned by Fox. It was common practice at the time for studios to divest themselves of their theatres. As a result, National General was spun off in 1952.

The company, then known as National Theatres, briefly entered the television field, but after an executive shift in 1961, National Theatres ceased owning and operating television and radio stations.

Business was looking good. In 1964, having changed its name to National General Corporation, the company struck a deal with industry giant General Electric (“GE”), to screen telecasts throughout their chain of live Broadway shows and sports. General Electric developed a specific projector for the task of displaying color television images capable of filling a theatre-size screen.

Known as Theater Color Television, a test launch was given at the Fox Village in Westwood, Los Angeles. Narrated by Ralph Bellamy, the program of live and filmed segments was carried via phone lines to the theater from National’s studio in Burbank.

So happy were national, they became distributor of the projector, given the name “Talaria”. Tapping into the youth market while debuting its newfound technology, National launched its closed-circuit network with a little help from The Beatles.

Over 150 movie houses across the U.S. and Canada showed a taped performance from the loveable mop tops. Reports indicated 700,000 teens enjoyed the show, to the tune of $1.5M.

Although NG hoped to increase this newfound revenue stream, the California Athletic Commission were monitoring state tax on closed-circuit exhibitions of sporting events.

At the start of 1963, NG continued its real estate push, establishing outlines to redevelop Carthay Circle — a Mid-West neighborhood in Los Angeles.

Plans involved new commercial space, as well as reconstructing the original Carthay Circle Theatre (Dwight Gibbs, 1926), with architect Victor Gruen on board.

Despite local preservation efforts and opposition from local homeowners, the Theatre met the wrong end of a wrecking ball in the summer of 1969. In its place sat new office space for National General Corporation.

Increasing its assets, the mergers and acquisitions department remained busy; Columbia Savings & Loan Association (1964), Mission Pak (1964), Sunset-Fox Plaza (1966), Great American Holding Company (1967), and Grosset & Dunlap/Bantam (1968).

By 1966, the company (which included Pierre Salinger as V.P. of advertising) operated 250 theatres in the U.S., and formed National General Pictures. The expansion included new offices in major cities. NGP diversified a year later, acquiring distribution rights for CBS Theatrical Films Division.

Based in Beverly Hills, company honcho Eugene Klein told the Los Angeles Times in 1966, “the greatest attraction on television is the motion picture”. When asked about home pay TV, the same executive later commented, “I believe it cannot and will not be successful.

Among the NGC-owned Fox West Coast Theatres screens in Los Angeles, included Carthay Circle, El Rey, Fine Arts, Bruin, Loyola, Lido, Iris/Fox, and the Vogue. The jewel in the crown was The Chinese Theatre in Hollywood.

Beginning in 1966, NGC and Warner Bros.-Seven Arts made efforts to merge. The multi-million dollar move dragged on for a number of years, but was blocked by the Justice Department in 1969, citing restraint of competition.

In 1967, and despite the odds, National decided to start making movies — producing between six to eight movies a year. Two years later, the company added National General Records to its portfolio, with a goal to produce LP’s, singles and tapes. The first offering for the newest subsidiary was Alex North’s soundtrack for A Dream of Kings (1969).

However, by 1969, NGP reported losses for the year at around $70M. Chairman Gene Klein attributed this to writedowns of its investment portfolio, totalling in excess of $95M. Not helping the bottom line were its acquisitions of the Great American Insurance Company, and Performance Systems Inc., — which franchised Minnie Pearl’s fried chicken outlets, based in Nashville.

The Tennessee-born singer might not have patronized the Hermosa Theater in California, where the NG-owned movie house screened I Am Curious Yellow in 1969. The infamous erotic movie caught the attention of the vice squad, citing California Penal Code 311.2 — an obscene material charge.

Despite local opposition, the Swedish movie became the 12th highest grossing film in the nation in 1969, behind The Love Bug, and Funny Girl.

Still, it wasn’t all gloomy. Producer and writer Mart Crowley’s seminal film The Boys in the Band (1970), had its premiere at the all-new National Theatre in Westwood — NGP’s third in the area.

However, NGP faced troubles one year after the release of The Todd Killings. At the time, NGP distributed titles theatrically for Cinema Center — owned by CBS. The network had invested close to $60M.

Amid executive shakeups at the company, rumors swirled that Cinema Center were looking to curtail production. Already facing financial losses, NGP started offloading assets. In 1973, NGC sold its entire chain to Minneapolis theatre chain owner, Ted Mann. The deal included the beloved, Chinese Theatre.

That same year, Klein stepped down from his position, and sold his shares.

Amid stockholder turmoil, the remains of NGP were bought by Cincinnati-based American Financial Corporation — a merger resulting in Klein back on board with a new contract.

By 1977, two former executives at NGP — Irvin Levin and Samuel Schulman — departed to become owners of the Boston Celtics, and Seattle Supersonics, respectively.

Longtime NGP publicist Herman Kass, passed away in 1981, though jumped ship to AVCO six years prior. Eugene V. Klein passed away in 1990. The onetime owner of Richard Neutra’s Kaufmann House in Palm Springs, also owned a desirable William Stephenson/Arthur Elrod property in the Trousdale Beverly Hills (demolished). In addition to his ownership of the San Diego Chargers, Klein’s championship horse, Winning Colors, won the Kentucky Derby in 1988.

Director Barry Shear passed away in 1979 at the age of 56.

The Todd Killings remained on the drive-in circuit well in to 1977, making its small screen debut in 1978 — albeit modified for television. Two years later, the film was retitled “A Dangerous Friend”, where it often played Cinemax at the unholy hour of 5AM.